Before the Canyon, before the River, before the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans there was the Lake. Before the Yellowstone, the Tetons, the Winds and the Redwoods there was the Lake. Before I peered through the thunder clouds of the Zambezi going over Victoria Falls, wandered in the scorching silence of Olduvai Gorge, took in the sage smell of the Serengeti, and even before I ever visited my storied Scottish Highlands, there was the Great Lake Ontario.

When you live near any of these kind of places you are subject to the power and majesty of that landscape. They are sublime. Weather, soils and settlement patterns, the availability of food, materials and employment, even your access to transportation infrastructure will be dictated by the place’s dominance. It is law, not abstraction. Our Great Lake Country up here in Sterling is that kind of place, and we are subject to Lake Law.

Now late into this wet Spring, we are reminded that everything we do is determined by a glance toward the Lake’s sky. We watch how the clouds are moving, see if the wind is backing, and note how the temperature is changing. Every weather report will earn a glance to the Lake on the map and where we live and work near it. We do this automatically; for us it is not really that big a deal. Even if everyone did this, would their sky be the same? Would they be subject to the same law? Would they understand?

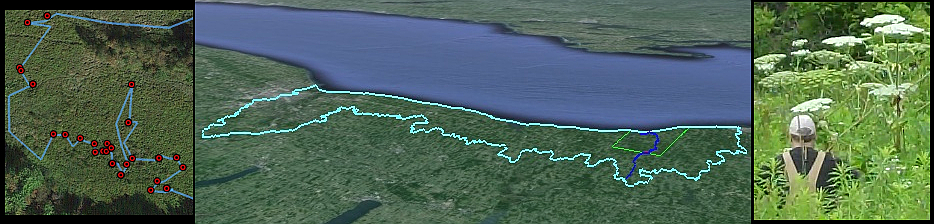

More than rivers of air move through Lake Country. The eagles, hawks, and turkey vultures have long passed through, but it is wet and warm enough that our punkies and their larger kin have already awakened to their duty. Everywhere our cottonwoods are sending out their next generation of seeds, like future stars moving into the sky. Golden rod is still only hip-high in the emerging meadows in the Cayuga Park area, and not really difficult to wade through as I hunt Giant hogweed. As I zig and zag on my hunt I see multifloral rose is in full bloom, but the milkweed is just getting started. The milkweed we want, the other two we really don’t.

By the end of June, Giant hogweed sends up a huge, fast-growing flower head. If allowed to go to seed, one plant can produce upwards of 20,000 seeds!

Giant hogweed is a dangerous invasive plant! Leaves, stems and roots contain a corrosive compound that will lead to serious skin damage. If you think you may have Giant hogweed on your property contact a USDA or DEC representative – without training or experience, do not chop, cut, mow, or otherwise handle any part of this plant.

In Sterling I also see and hear the first big flushes of the development season, as many of us are optimistically and energetically building barns, marking roads, working with consultants and committees, readying pipe for new public water systems, and weaving zigzag fashion through our town’s telling institutional history of learning to live with land. Like plants in our landscape, some development we want and some we don’t. Like some organisms from far away, there is development we bring here that is welcome, desirable, and productive. But like other exotic plants and animals, there are activities we pause to consider: we have to think about what it means to let them in, take root, and grow. We have to consider if we can manage it under Lake Law.

The more time I spend in the Lake Country I realize that choosing what we want in this special landscape – when we really are presented with a decision – is increasingly a matter of our harmonizing our actions under this very real, but invisible Law. By Lake Law, I’m trying to describe the ecological conditions here that require a unique and careful kind of resource planning and development; one that blends the science and regulations of modern land use practices and ecology with practical human need for sustainable communities.

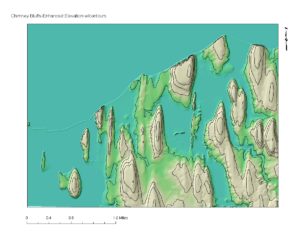

Lake Law began when our town was submerged, our drumlins smoothed over, and draped with silty Lake bottom sediments. Long ago, overhead of where I wander to take out invasive plants, the waters of Glacial Lake Iroquois deposited fine sediments onto my land, all the while eating into an East-West line of wave-cut and sculpted drumlins along Sterling’s Southern boundary.

As Glacial Lake Iroquois drained it kept shaping the Northern Cayuga County landscape. Source: lvanvlee8’s Flickr account at https://www.flickr.com/photos/24994567@N06/

This is why my mushy, silty soil with shallow hardpan discourages pine and corn but when treated respectfully is a little more accepting of spruce and oak. Just as any visitor to the Bluffs has seen – and any Great Lake shore-line owner knows all too well – the Lake’s ability to shape land, remove buildings, and take out roads is considerable. The power it has today was every bit as dramatic during the Pleistocene.

Surface Geology, NYS Library

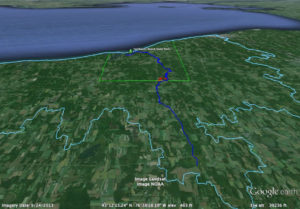

But the Ice Age did not deed all landowners the same ecosystem service and resource use potential, and herein lies the crux of the current decision facing the Town of Sterling. Owners of a promising bed of glacial sediments near Martville want to build a small sand and gravel quarry, not far from Sterling Creek and its wetlands. The developers have been tracking the complex state and local permit process with determined zeal, and must persuade the town and the residents that the technical and environmental feasibility of the project warrants the impact their operation will have on neighbors and travelers.

If approved this project will become the first industrial activity next to the 45 ½ mile long Sterling Creek. The quarry will be 20.5 stream miles above the Fairhaven Beach State Park – just about 6.5 miles as the crow flies.

Sterling’s modern history of land conservation and planning dates from New York State’s first acquisition of key wildlife habitat on parcels just West of Sterling. However, even though the State did not buy land in Sterling, during the 1930’s they did support habitat improvement along the Lake. Next to the Sterling Nature Center there is a conifer stand John Weeks helped plant back when the state was first protecting wetlands in the area. But regional planning involving Sterling didn’t come about until the State of New York created the St. Lawrence-Eastern Ontario Commission (now–defunct). For a time Cayuga County’s Town of Sterling formed the Western gateway to the many towns in SLEOC; and considering that Sterling didn’t have zoning at the time it is fun to think about what impact that participation had on the regional identity Sterling developed after RG&E announced they would build a nuclear power plant on 3,000 acres of farms, forests, and wetlands they had purchased through a dummy corporation.

The many decisions and details leading up to the creation of the Cayuga Park are beyond the scope of this blog entry, but soon after SLEOC ended in the last years of the 20th Century, local zoning and land use planning in Sterling took root after Cayuga County mapped the forests and wetlands in Cayuga Park, and the State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation purchased conservation easements on those same properties. In one huge, visionary step, the Town of Sterling entered into a regional planning partnership with Cayuga County and a State agency. This means that local planning and zoning is still fairly young in Sterling. But where it is youthful, it is also rapidly gaining experience and expertise.

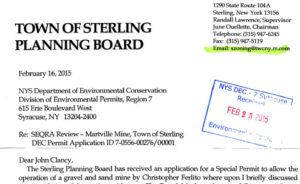

The Town’s Council, Planning Board, and Zoning Board of Appeals are doing a commendable job coordinating many voices in this process. Please note, however, that State law has not been standing still since New York towns like Sterling got into the planning and zoning game. Following New York State law, in 2005 Cayuga County adopted “Intermunicipal Review of Local Land Use Actions” by establishing a 239 Review Committee, so–called because it follows Sections 239-l, 239-m, and 239-n of New York’s General Municipal Law. When the quarry developers asked for a use variance to begin mining along Sterling Creek, the Town had to notify the County of the application. The County’s 239 Committee identified many safety and neighborhood quality-of-life concerns, and has recommended the Town of Sterling not approve the sand and gravel mine.

The Town’s Council, Planning Board, and Zoning Board of Appeals are doing a commendable job coordinating many voices in this process. Please note, however, that State law has not been standing still since New York towns like Sterling got into the planning and zoning game. Following New York State law, in 2005 Cayuga County adopted “Intermunicipal Review of Local Land Use Actions” by establishing a 239 Review Committee, so–called because it follows Sections 239-l, 239-m, and 239-n of New York’s General Municipal Law. When the quarry developers asked for a use variance to begin mining along Sterling Creek, the Town had to notify the County of the application. The County’s 239 Committee identified many safety and neighborhood quality-of-life concerns, and has recommended the Town of Sterling not approve the sand and gravel mine.

But the County’s 239 Committee did not say the Sterling Creek’s water quality or wetlands were in danger from quarry development. They may have missed something: if the mine’s development plan is updated to correct an apparent intention to build in the wetland, and if the operators follows the plan approved by the NYS Department of Conservation – the lead agency spearheading the permit review process – the wetlands should be protected.

But Town and County officials must be confident the project will not take place in the wetland before the project is given final approval.

Lake Law began in the Ice Age, but the geographic and cultural power of Lake Ontario on our land and lives endures. Sterling residents may have the political clout of wetland law with them if they choose to delay quarry development along Sterling Creek, but the apparent extension of the mine footprint into the Sterling Creek wetlands is probably just a cartographic oversight. Regardless, it must be corrected; hence the notion of delay. However, local residents and officials have a right to oppose – and possibly stop the quarry project – it if they agree with the County’s recommendations. Quarries do create noise, dust, and often impact nearby wells. Happiness, quality of life, peace and quiet: they all matter.

If the developers change their map to prove they will not mine in the wetland I myself will not oppose the project; that removes it from regional impact. But are road hazards, noise, and dust really only local neighborhood concerns? In a matter of hours, the Town of Sterling zoning and planning boards will consider the variance requested to quarry sand and gravel alongside Sterling Creek. But here in Lake Country, the Creek and the sky belongs to the Lake. All the land, the plants and animals’ lives – and ours too – belongs right here in Sterling, on the Lake. The mystery and majesty of the Lake County landscape is what brings and keeps us here, and the Lake Law that made and keeps it so is the force within it. Looked at in this way, our path this Spring is not crooked or zigzag: our responsibility to the Lake, the Lake’s Land, and the quality of our neighbors’ lives is as easy to see and read as the Lake’s sky.